Gwen Stefani. She was the first white woman I remember seeing wearing a pottu. Or as she called them, bindis. Whether it was for a music video or a photo shoot, I can’t remember – but those jewelry dots were plastered all over her forehead. I remember feeling confused. I loved No Doubt and was still a fan of Gwen, but there was something about her use of my culture that made me feel… icky.

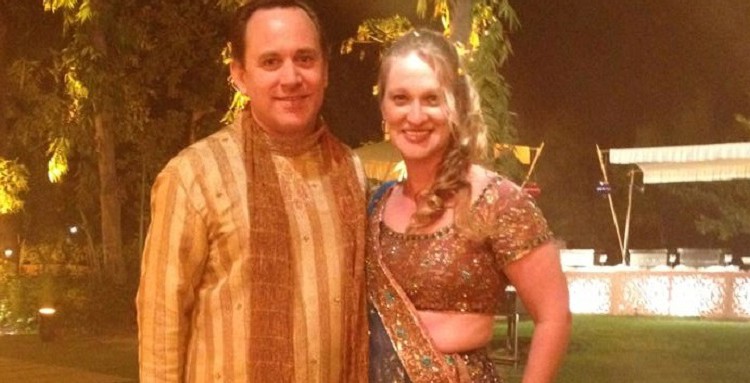

Somewhere in my college years, I learned a term that gave that feeling a place to land: cultural appropriation. Because that’s just what cultural appropriation is – icky. Seeing an other-culture person wear your culture’s traditions can be downright triggering. Alternatively, the world is jam-packed with awesome folks like my friend Stefanie. Stefanie is one of the warmest, loveliest people I know. She was recently invited to Delhi for her good (Indian) friend’s wedding. Naturally, I offered to let her raid my closet. In the picture seen above, Stefanie is decked out in full South Asian regalia. She looks radiant. She is also the epitome of grace and respect – the antithesis of cultural appropriation. How do we know when culture is being exchanged versus appropriated? It’s a sticky thing to pin down. Jarune Uwujaren has crafted the best definition I’ve read, delineating the two.

Here’s where I’m at with it. As a perennial dot-wearer, I have no issue with other-culture folks wearing pottus. I wear a pottu every day. Growing up, this was how I saw my Amma live our Tamil culture. I came to see pottus as a celebration of beauty and womanhood. Living in Oakland, I worked as an advocate for sexually exploited minors. For reasons beyond my comprehension, my clients were crazy about my pottus. They LOVED them. And not the glitzy bling pottus – they loved the simple, black circle. My pottus became a platform for connection, a cultural window to peek into each other’s worlds.

I remember one girl in particular, who I’ll call Suzie. I used to see Suzie every week during a Zumba class my agency taught in juvenile hall. During one class, she asked if she could wear my pottu. She was ecstatic when I gave it to her. She saved that pottu for weeks on end. Every time I came into juvenile hall, she would press that little, black dot on her forehead and wave wildly at me from her jail cell window. My day was made better out of those 30 seconds of giggling, a shared mutual affection. Seeing her caged behind that glass barrier was mind-numbingly depressing. Seeing her face light up every time she put on a pottu broke my heart open, awed by her resilience and the sheer amazingness of her spirit. Seeing non-brown folks wear pottus doesn’t bother me one bit.

What does bother me is this “bindi” business. To me, they are pottus. In Gujarati, they are chandlos. In Marathi, they are ticklis and in Bengali they are teeps. The prevalence of Hindi to define every South Asian term is both alienating and boring. The South Asian sub-continent is a meld and overlap of subtle and distinct cultural variations. When did we, as South Asians, decide to stop recognizing and acknowledging each other? For sure, Hindi terminology is easy. Because it’s always easy to buy into a majority. And in buying into a majority, we “other” a minority community.

To “other” a community is to define their value against the value of a better/majority/more powerful community. Time, understanding, and appreciation are values which can only be afforded to a majority community. No one wants to spend an additional 10 minutes explaining that in our language, where we’re from, we call that thing a pottu. So we’ll bypass the annoying anthropology lesson and just call it a bindi.

I wondered if this is what happened in Raisa Bhuiyan’s article “Not Your ‘Fashion Dots’: The Continuous Appropriation of Bindis”. I don’t imagine that by always using the term “bindi”, Bhuiyan intended to alienate and exclude me. But she did. Cultural appropriation is defined by privilege. But privilege is defined by more than just ethnicity. Privilege is also defined by education, language, sexual orientation, financial circumstance, the list goes on. Very few of us are wholly on one side of the privileged/not privileged spectrum. There is a cost to making blanket statements against ALL (insert majority ethnicity) who practice (insert minority cultural tradition).

Blanket statements serve only to erase identities, to “other” a particular group of people (no matter how privileged that group of people may appear to be). In the process of advocating against marginalization, we are simultaneously ignoring our own elements of privilege and denying ways in which any “privileged” person may have been marginalized. So the white woman who found belly dance as a joyful way to reconnect to her body and move beyond her sexual assault? Cultural appropriation. And the little girl who feels special when she wears a pottu in her jail cell? Cultural appropriation, Selena Gomez style.

Conversations that challenge established privileges and powers are vital. As Uwujaren puts it, conversations around cultural appropriation aren’t “a matter of telling people what to wear. It’s a matter of telling people that they don’t wear things in a vacuum and there are many social and historical implications to treating marginalized cultures like costumes.”

Hopefully, these conversations help all of us become better at treating each other with basic love and respect. We do not own the things of our culture. They are material things that we imbue with meaning, a collective sense of self. Material things will always be subject to change. What we own is the right to speak up for ourselves and to speak up for those around us. What we own is the right to create and live in a world that values who we are, however we are.

TamilCulture aims to promote healthy dialogue about issues affecting Tamils worldwide. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect TC’s editorial policy.

Meena Serendib

Meena Serendib