In the Tamil-Canadian community it seems as if we all know at least one person who has gone abroad to study medicine. Perhaps it was a friend, family member, classmate, or someone you heard about through your parents. In a culture where the tendency of parents to brag about their children is all too pervasive, many young people in the Tamil diaspora face immense pressure throughout their lives to be successful.

From witnessing numerous “grown up” conversations over the years, the crowning pinnacle of achievement for many Tamil parents is seemingly to lay claim that his or her child is a doctor. When the trend of students going to the Caribbean and the UK to pursue medicine subsequently began to pick up in the late 2000s, I was not surprised to learn that many happened to be Tamil.

According to a report by the Canadian Residency Matching Service in 2010, students who opt to study at international medical schools do so for a wide array of reasons; 27% had outright never applied to a Canadian medical school while 64% had only applied once. Many of these applicants are simply not competitive enough to be admitted into Canadian medical schools and looking for a “quick route” to become doctors, decide to study abroad as many of these schools do not hold stringent entry requirements.

Upon reading several articles about the difficulties faced by international medical graduates (IMGs) upon returning to Canada, I met with a graduate from a Caribbean medical school named Jegan who had just written his Canadian licensing exam. Like many IMGs Jegan had completed an undergraduate degree at a Canadian university before the idea of studying medicine abroad came to mind. After completing all the necessary prerequisites for Canadian medical school admission such as having studied very hard during his undergraduate years in order to attain a high GPA, Jegan also wrote the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT). However, dissatisfied with his results, Jegan soon realized that his lifelong ambition of going to medical school could potentially never happen.

Although the average Canadian medical school student applies an estimated three times before gaining acceptance, those who are rejected after their first or second attempt often consider the prospect of international medical schools. Upon hearing of a family friend who had recently started medical school in the Caribbean, Jegan decided to take a chance and go abroad in order to continue pursuing his dream.

Many of Jegan’s colleagues also found difficulties in the Canadian medical school admissions process and held undergraduate degrees from Canadian universities with the goal of wanting to become doctors. Others held degrees in the life sciences that they realized were not practical for direct careers after graduation, and not wanting to “waste time”, decided that attending an overseas medical school could provide them with the job security that they desperately sought.

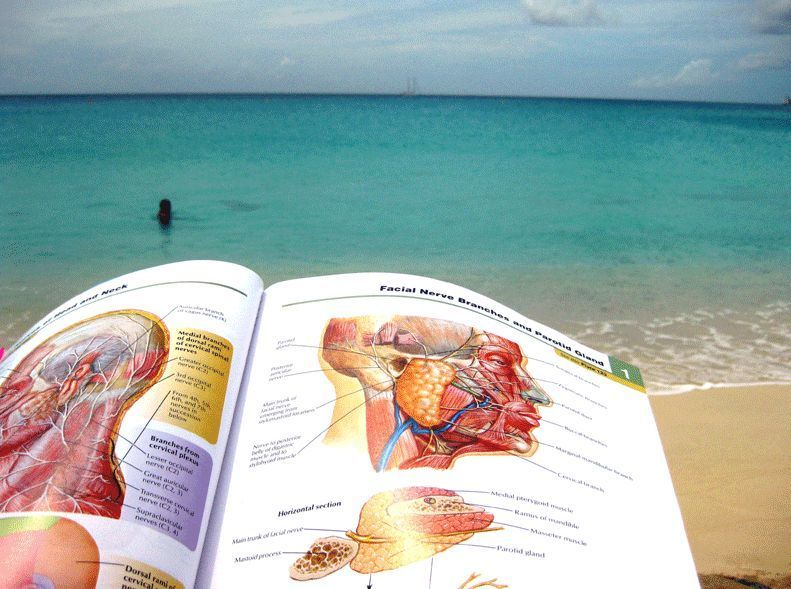

As with many medical schools in the Caribbean, Jegan’s medical training consisted of a four year program. The first two years focused on basic science training while the final two years shifted focus towards clinicals in approved cities in the United States. During this clinical period, students are required to write board exams. The first two exams are completed towards the United States Medical Licensing Exam (US MLE) while the third exam is completed for the Canadian equivalent of the Medical Council of Canada Evaluating Exam (MCCEE). These exams are not required by North American medical students and are explicitly designed to weed out “substandard graduates” who have overwhelmingly been individuals who have gone abroad without prior undergraduate degrees.

In the final year students subsequently apply for residencies in the US or Canada. However, those interested in residencies in the US face the difficulty of not only going through the American Visa process, but the reality that most American institutions will prioritize American students or only accept American applicants. Alternatively in Canada, each university holds a set and limited number of residency spots available for IMGs.

This is where the idea of a “quick route” to medical school becomes muddled with the very real challenges faced by IMGs who wish to return to Canada and practice as doctors. As echoed by Sten Ardal, CEO of the Centre for the Education of Health Professionals Educated Abroad in Canada, “It’s horribly competitive [for IMGs]. They have invested money along the way – there’s a lot of investment – for a relatively small chance of getting accepted into the residency.” Ardal’s statement aptly reflects the experience of Jegan as he described to me the two years following his graduation in which he was without a residency and ultimately out of work.

Not having secured a residency can leave many IMGs feeling depressed and disillusioned given the false assumption that by their acceptance into these overseas medical schools they will be guaranteed residencies upon graduation. Jegan described several students who had given up on their dreams of becoming a doctor as a result.

Given the great expenditures that comes with attending an international medical school, not only including the expected tuition and living fees, but the costs of examinations during the clinical process (which if one fails they are expected to keep paying until they pass), alongside the cost of applications for residencies with a single residency application ranging from $5, 000- $6, 000, many parents eventually come to terms with the reality of the financial burden they have put themselves through in order for their children to become doctors. Carrying debts as high as $300, 000, when IMGs are not immediately granted residencies in North America both children and parents alike can find themselves in a financial limbo. Having invested in sending their children overseas with the expectation that they would leave as doctors essentially put on hold until the granting of a residency.

Fortunately for Jegan however, his tireless volunteer work and dedication to keep re-applying in the years following his graduation eventually led to him being granted a residency at a Canadian university. Jegan has since gone on to complete the Canadian licensing exam, and hopes for a positive result in the following month. This is the final step for IMGs as well as Canadian medical school graduates towards becoming fully licensed doctors in Canada.

As I spoke with Jegan, although he was confident in his ability to pass, he described to me the notoriously difficult passing rates and indicated that those who pass and score in the highest percentile are typically those who studied in Canadian medical schools.

According to the Canadian health news site HealthyDebate.ca, given the barriers faced by IMGs upon returning to North America with respect to the residency and licensing process, many are not surprisingly less satisfied with their professional and personal lives relative to their North American counterparts.

However, it is important to note that the experiences of IMGs have not all been negative. While a number of internationally trained doctors may not have secured North American residencies or passed their licensing exam, there are many like Jegan who fully expect to live and breathe their dream of becoming doctors. Jegan described his sleepless nights while studying for exams as an undergraduate, and months of locking himself up in his room while studying during his clinicals. In our conversation, he revealed his unwillingness to give up even after not immediately being granted a residency, and I felt his genuine passion for his career as he spoke about his experiences. Although he was cognizant of the barriers many IMGs face in returning to North America, his story stands as illustrative of how absolute dedication, passion, and perseverance can ultimately drive and determine success. I am confident he will soon have his dream fully realized.

As my talk with Jegan came to a close, I asked him to sum up his IMG experiences to which he shared the following:

“If I had to do it all over again I would. This is what I’ve always wanted to do. But I would advise people to do their research. It’s a huge investment with no guarantee. Don’t assume that you’ll automatically come back to Canada as a doctor. Lastly, make sure the pressure you feel to go abroad comes from you and you alone. Those that really want to do it for themselves are the ones that end up being successful.”

Related Article:

Life as a Medical Student: Resilience, Determination , and Sacrifice

Shanelle Kandiah

Shanelle Kandiah