An open letter to the Tamil girl who wrote “An Open Letter to Young Tamil Men”.

Dear Niveda,

I do not purport to speak for the “Young Tamil Men” your letter is addressed to. I do, however, speak for myself and possibly other women, whose voices you have taken the liberty to assume in your letter.

It is surprising and regressive that while claiming to speak for female sexual autonomy and freedom from the oppressive demand for “chastity”, your arguments ultimately revolve around ideas of what is “marriageable”. There is, it seems, an unquestioning acceptance of the institution of marriage and its dominant construct in society. More worryingly, your letter seems to imply that all women, after experiencing all the “fun” that youth has to offer, must ultimately submit and resign to this institution.

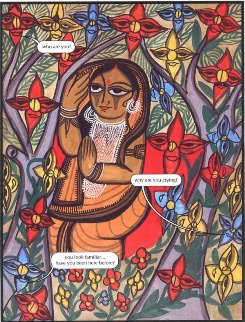

Even your example of Sita from the Ramayana, and your presumption that most men grow up with the idea of a “modest, angelic Sita” (ignoring all the multiple versions that challenge this image of Sita), is linked to the question of who men imagine they will marry and what attributes, according to them, constitutes the essence of a marriageable woman.

Would you argue with the same force, let’s say, for the sexual freedom of married women, their right to get “horny” and be “sexually active”, as you refer to it? Or is it your argument that these urges and the freedom to explore them last only as long as a woman is unmarried, perhaps in contradiction to your own argument for women’s sexual behaviour being a matter of nature and instinct free of fetters.

Let me make myself clear to avoid ambiguity. I am a feminist and believe strongly in women’s sexual freedom and autonomy. But to reduce this to having fun in your “teens and twenties”, and to freely having (multiple) sexual partners to fulfill sexual urges, is reductive apart from being unrealistic. To imagine and depart from the premise that a majority of men are for the most part “sexually active” and constantly fulfill their sexual urges is perhaps equally so.

It is maybe a reductive and misplaced understanding of liberation that has contributed to the kind of images we see in popular culture as a counter to the image of the chaste and pure woman. The dominant image of the new woman in mainstream consciousness – while not de-sexed and while proclaiming her readiness for sexual conquest – is equally an object of such conquest. This is because the ideas and vocabulary in essence remain the same – of human beings as “objects”.

Assuming the Rajnikanth movie you refer to is a starting point for a meaningful debate on the representation of women, I remember the “strong sex appeal exuding” Neelambari as a character who gives up a normal existence for having been rejected by the hero. While you rightly refer to her as typifying “evil” and point out the tendency to depict women as either “modest and righteous” or “sexually active and evil”, you seem to ignore an important attribute to her character – her craving for endorsement by the man who “rejected” her.

In a sense, there is no difference between her and the heroine, both of whom derive the legitimacy for their existence from the man, although in different ways. By referring to the choice the hero makes as symbolic of how women are imagined and perceived, you seem to suggest that choosing Neelambari (which would mean her being endorsed by Rajnikanth, the man) might have been a cause for women to celebrate.

Your essential argument that women can be both sexually active and “righteous” is as polarizing as the arguments you seek to attack. The notion of righteousness itself carries with it the idea that you must be endorsed in some manner by the establishment – if not the one that demands chastity from women, then some other. There is also the inevitable subtext to “righteousness”. It implies a very self-conscious sense that what one is doing is right, and the belief that this entitles one to judge other’s actions with a moral compass.

Before I conclude, let me draw your attention to a debate that you may find interesting – find here Sinead Connor’s open letter to Miley Cyrus, and here, the responses of a cross-section of women in the age group 18-24 to Miley Cyrus.

Finally, while no one has the right to appropriate feminism and every competing point of view must have its space, the tendency to equate liberation with libido needs challenge. To not do so would be to ignore the brave efforts of our foremothers in fighting for real and substantial equality; in making our voices heard – in both the private and public spheres – and would reduce feminism to a mere pursuit of individual gratification.

Preeti Mohan is a practicing lawyer in the courts in Tamil Nadu. She is deeply interested in socio-legal issues and their impact on the evolution of the law, and juxtaposes academic analysis with the real-life experiences of court practice. She is interested in the study and analysis of the Indian constitution, its values and norms and has published papers on the same. Preeti is drawn naturally to politics and philosophy, and the exploration of their inevitable and intriguing connections with the law.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect TamilCulture’s editorial policy.

Originally published in The Alternative.

Related articles:

Guest Contributor

Guest Contributor