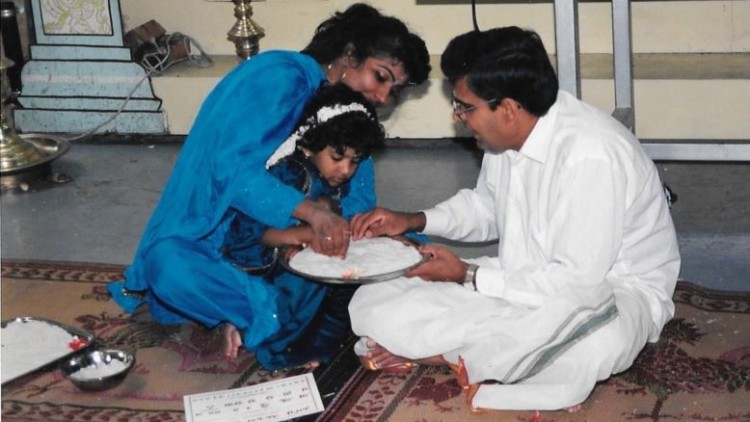

My favourite childhood photo captures me at age 4 perched on my mother’s lap, sitting on an intricately woven pai alongside an aiyar. In this photo, the aiyar is guiding my hand through a bed of dry rice grains to form the first letter of the Tamil alphabet, அ (Aa-na).

Here, I am participating in the ceremonious Hindu custom of initiating a child’s educational pursuit by tracing letters of the alphabet into rice, an auspicious symbol of prosperity and growth. Seventeen years later, I look upon this photo and am overcome with a sense of estrangement as I ask myself, “how did I let my culture escape me?”

At 21 years old, I realize that I have done myself a disservice. I can barely form a coherent sentence in my language, letters are foreign squiggles to me, and I find myself performing exaggerated gestures to communicate with my non-English speaking grandma. This is certainly not due to a lack of exposure to Tamil, but more as a result of a conscious distancing.

Growing up, I willfully practiced negating associations with my cultural identity to align myself in proximity to whiteness – what I perceived to be the ultimate measure of beauty and success. All of my dolls were named variations of Sarah and Ashley because I cursed my ethnic name, flushing at the automatic discomfort upon its arrival on the attendance sheet.

My mother was given strict guidelines as to what she could and could not pack as lunch for me, forbidding anything attached to my background on account of being “smelly” and “funny-looking”. As a teenager, I rolled my eyes at Tamil films and shows, assuming them to be melodramatic and unintelligent. I used the term “white-washed” as a self-descriptor, adorned as an armour of pride. In hindsight I recognize I was mistaking pride for self-hatred.

The rejection of my cultural identity is a direct dismissal of immigrant strife, which serves as a common thread linking Tamils-Canadians across the country. Many Tamils came to this country as refugees after the life-shattering 1983 riots in Sri Lanka. Fleeing from trauma and having to re-establish life as a visible minority was an extremely painful process to say the least. My father recounts being denied access to buildings due to language incompetency, and being on the receiving end of piercing racist remarks from service providers. He tirelessly worked at underpaying, labour intensive jobs as a way to perpetuate his right to exist within a society that jeered at his presence.

Yet as a result of his hard work, my sisters and I lead comfortable lives benefiting from Canadian institutions and programs. I have come to realize that in denying my culture I was denying my parents’ struggle as immigrants. I was denying the plight of my people, and I was asserting that my status as a Tamil-Canadian was not structurally disadvantageous.

I am not unique, however, in the compulsive need I felt to mimic whiteness. In fact, the inherent inferiority to white bodies harboured by Tamils can be traced to the British colonization of Sri Lanka. During this period, cultural assimilation via religious conversion and English language laws rooted a structural power dynamic, favouring those who adhered most closely to European ideals. Burgher populations descending from Portuguese, Dutch and British settlers were given increased autonomy by the British constitution, breeding a cultural divide that upheld citizens who most closely mirrored whiteness.

Tamils were tremendously disadvantaged by this structural inequality, and committed to adapting whiteness as a way to gain approval from their European rulers. This sentiment is echoed in many first generation Canadians like myself, who often align themselves with their favourite film and television stars. Seeing predominantly white bodies excel in media representations of reality, while characters that look like them routinely serve as punchlines for racially charged jokes, inevitably ingrains the notion that success is equated to whiteness.

Seventeen years later, I look at the அ imprinted on the silver plate of rice and feel a sense of overwhelming responsibility to make up for lost time. A responsibility to honour the violent struggle of Tamil refugees. A responsibility to counteract the domineering forces of colonization and media representation. And above all, a responsibility to my parents, who despite numerous obstacles consistently stressed the importance and beauty of Tamil culture. As I start to reclaim my cultural identity, I must remind myself that assimilation takes willful participation, and it is up to me to immerse myself in my language, understand my history and contribute to spaces that uplift Tamil communities.

Related articles:

Finding Tamil Identity

What Does It Mean to be Tamil? A Personal Reflection

Why Do Westernized Tamils Hate FOBs?

Brannavy Jeyasundaram

Brannavy Jeyasundaram