Saravana Bhavan doesn’t look like a house of secrets. Its dining room at the corner of Lexington Avenue and 26th Street is clean and bright and often attracts a line out front. It doesn’t advertise because it doesn’t need to; the fact that it’s one of the world’s largest chains of vegetarian restaurants — 33 in India, another 47 in a dozen other countries — is considered too obvious to its core clientele of Indian expatriates and tourists to be worth trumpeting. In a city overwhelmed with underwhelming north Indian food, Saravana Bhavan is the standard-bearer of the delicacies of the south, but it makes no effort to educate the uninitiated. If you don’t know what a dosa is or how to eat it, you’re on your own.

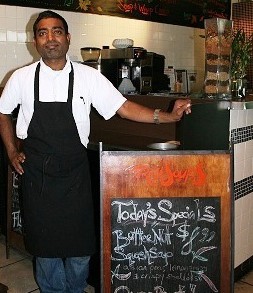

The man behind the chain is an elusive 66-year-old named P. Rajagopal. Among his peers in the restaurant business in Chennai, the south Indian city where Saravana Bhavan is headquartered, Rajagopal is a legend. “He brought prestige to the vegetarian business,” said a restaurateur named Manoharan, who runs a competing chain called Murugan Idli. “He made a revolution.”

Born into a low caste in a remote province, he came to rule a field that was once the sole domain of Brahmins, cleverly updating their traditional fare in a setting that was both respectable and unpretentious, thereby catering to India’s middle class at just the moment it emerged. Today he employs more than 8,000 people in Chennai alone. His workers enjoy benefits fantastic enough for Silicon Valley (pensions, TVs, education), inspiring among them fierce loyalty to Rajagopal. Every day thousands of pilgrims come to pray at the temples he built in the village of his birth, and a hundred thousand come to eat in his restaurants.

His business model is so seemingly foolproof that the company has acquired an air of invincibility, even as its founder became sullied with scandal. As Saravana Bhavan went global, Rajagopal was charged with murder, found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Yet he served a total of only 11 months, and today he’s free to continue his expansion — next stop Hong Kong, followed by Sydney, Australia. And then, if his health holds out, building his first luxury hotel.

Saravana Bhavan specializes in the holy trinity of south Indian snacks known as tiffin: dosa, idli and vada. All are made from ground rice and lentils, with remarkably different results. Dosas are crispy golden crepes that are most deliciously served with a masala of potato and onion; vadas are deep-fried savory doughnuts; and idlis, the south’s staple food, are pure-white saucer-shaped steamed cakes. At most branches of Saravana Bhavan in Chennai, you can also find for sale a little book titled, “I Set My Heart on Victory.” First published in 1997, the book is Rajagopal’s memoir and manifesto, a curious blend of mythmaking and self-effacement.

His story begins in 1947, 10 days before India’s independence from the British, when he was born in the vast brushland in the southern state Tamil Nadu. His village, Punnaiadi, was so inconsequential that it didn’t merit a bus stop; his home was a shack with mud-and-cow-dung floors. Rajagopal writes that he quit school after seventh grade, left home alone and took a job wiping tables at a cheap restaurant in a distant resort town, where he showered in a waterfall and slept on the kitchen floor. But he was proud of his work, especially after the restaurant’s tea master inducted him into the mysteries of making a perfect chai.

When he was a teenager, he moved to Chennai, then known as Madras, and in 1968 opened the first in a series of tiny groceries on the outskirts of the city. One day in 1979, at his grocery in a neighborhood called KK Nagar, a salesman made a casual remark: He’d have to go all the way to T Nagar for lunch because KK Nagar didn’t have any restaurants.

A century ago, there were virtually no restaurants in all of Chennai. “It’s a country that was very conservative about eating out,” said Krishnendu Ray, a food-studies professor at N.Y.U. When Rajagopal was born, the restaurant scene consisted of little more than Brahmin hotels: modest affairs catering to the traveling upper caste, whose dietary rules dictated that they couldn’t eat food cooked by any caste but their own. As a member of the Nadar caste, Rajagopal wouldn’t have been allowed to eat in most Brahmin hotels, let alone run one. But by the time he came of age, entrepreneurs from other castes had begun to meet Chennai’s increasing appetite for dining out…read more.

-Images courtesy of The New York Times

Guest Contributor

Guest Contributor