July 1st is of utmost importance to all Canadians. It marks the day the British North America Act came into effect giving birth to Canada, a country that is today home to 34 million. Canada is a free, prosperous and multicultural nation developed via contributions through people from all four corners of the world. As a citizen of Canada, I take pride in my country and embrace all the values it has taught me.

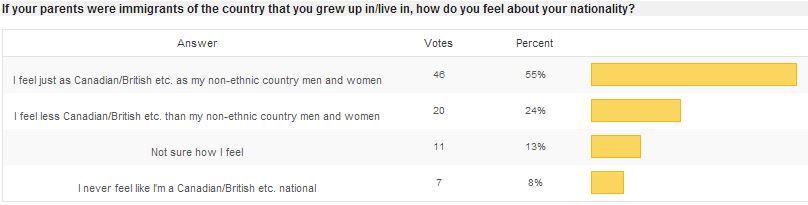

I consider myself Canadian before anything else. I identify with any Canadian citizen, regardless of language, ethnicity or religion. Yet I concede that this did not come naturally to me throughout my life. A lot of thought has gone into figuring out who I am and where I stand in this country I call home.

When I lived in downtown Ottawa, I would sometimes do grocery shopping at the local market. During one of these trips I didn’t have many items, so I decided to go to the express checkout. As luck would have it, there was no one in line. The interesting part about this particular venture was the exchange I had with the cashier. While scanning my items, she looked at me with curiosity and asked “Are you Ethiopian or East African? I’m Ethiopian and you look identical to my brother.” In response, I told her that I was from Toronto. “But where are you originally from?” she inquired further. I told her that I was Sri Lankan because I knew that was what she was really wanting to know.

This is not the only time that I’ve given this response to questions about my origin. It is true that my parents are from Sri Lanka and that I grew up with the culture, language and traditions thereof. But I have never visited nor lived in Sri Lanka. I know nothing of the Sri Lankan lifestyle or society firsthand. From a national standpoint, it seems reasonable that I call myself Canadian. However, society often expects me to identify as Sri Lankan since on the surface it seemingly makes sense for me to do so.

I began thinking about other individuals who would fall into this quandary. If such a question were posed to an Afrikaner from Johannesburg, society would not compel him to say he is really of European heritage whilst living in South Africa. If an African-American woman said she was from Atlanta, society would not question whether she’s really from the United States. And if a Jewish man said he was from Budapest, society does not interject stating that he is actually from Israel. Although these examples are acceptable now, this acceptance is the result of a long battle for such recognition.

Take South Africans of Indian origin as an example. Indians arrived on the shores of South Africa in the mid-19th century as indentured labourers. Since English was the de facto language under British colonial rule, subsequent generations adapted English as their first language, thereby forgetting much of their mother tongue. So would it be more appropriate to call this group Indian or South African?

While their origins can be traced back many generations to India, to call them Indians seems erroneous as their society and culture has evolved separately from their co-ethnics in India. Though certain aspects of their culture may be derived from their native India, this connection does not imply that they will follow the same norms of the people of India. As a result, it makes sense that they identify as South Africans since their society, culture, language and way of life reflects that of South Africa.

Similarly, African-Americans arrived on the southern shores of the United States during the slave trade of the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries. It was by force that they forgot their language, culture and ancestral names in order to work enslaved in plantations as property. Consequently, they were forced to adopt the culture imposed upon them.

After the abolition of slavery in the mid 19th century, a significant number of African-Americans repatriated to West Africa. Those who voluntarily returned to Africa through the Liberia scheme differentiated themselves from what they called the “tribal Africans” indigenous to the area. Though the two groups share the same skin colour, African-Americans termed themselves “Americo-Liberians” with stronger ties to America over Africa despite the hardships that they and their ancestors endured. Even within this repatriated population, the diaspora felt it was more appropriate to identify as being of American origin rather than saying that they “returned home”.

Keep in mind that African-American and Indo-South African cultures – while unique in themselves – area vital fabric of what is America and South Africa today. However, the difference between my standing and theirs is that the latter came about as a result of force. In most cases, these groups were forced to migrate to their adopted countries. They were also forced to “forget” what culture they had and knew from their lands of origin. In generations past, there was virtually no communication with the Old World to sustain culture.

My situation, however, is one that is associated not with force but with freedom. My parents chose Canada for a better life and to leave a country torn apart by discrimination, hatred and a lack of freedom. In Canada, I have the freedom to speak my mother tongue and practice my religious and cultural beliefs. Thanks to globalization and advances in technology, I have the freedom to maintain connections with family in Sri Lanka and access films, music, TV stations and serial dramas that are popular among Tamils in Sri Lanka. I have the freedom to wear Tamil clothing, study Tamil literature, and celebrate Tamil festivities while living in a tolerant, multicultural nation.

We are all products of our environments and we adapt to changes within it. Canada is the product of the many contributions towards its development and growth from many different peoples, each bringing in cultural aspects that we have now adopted as our own. I am taught that criticizing my government – whether it is serious or satirical – is not discouraged. I am taught that I can ask for government service in English or French without denial. I am taught to question what the media tells me and to not rush to conclusions based on how something is portrayed. I am taught to work with a code of ethics and dignity, and that it is okay to walk out on the job if my supervisor does not want to comply with proper protocol. These traits – among others – make me Canadian.

We are very lucky to live in this time period for we have the choice evolve as Canadians while preserving our roots and retaining ties to our Sri Lankan brethren. We would not have had this option 50 or 100 years ago for I believe our outcome would have been akin to Indo-South Africans and African-Americans. As our community evolves with future generations born in Canada, a stronger identification with being Canadian is inevitable. The key rests in our choices.

I am happy to identify myself as Canadian. But I can also call myself a Sri Lankan to the extent to which what I do culturally reflects it. Should I choose to sit at home in a sarong, eat string hoppers and watch Saravanan Meenatchi on Star Vijay at home – or should I choose to sit at home in pajamas, snack on some Nanaimo bars and watch CBC’s The Rick Mercer Report or RDI’s Et Dieucréa… Laflaque – I am truly a Canadian national representing and contributing to the Canadian lifestyle, simply because I cherish the one virtue that Canada has given me – freedom.

We are a generation that came about as a result of immigration to a country in search of a better life. We are the pioneers for change, and it is up to us to strike a balance between what we’ve learned as Canadians and what we’ve retained from our respective cultures. I believe the defining factor that shows we are Canadian is our values. Canadians are a people who believe in equality, respect for cultural differences, freedom and peace. Being a bilingual nation from coast to coast shows that we respect cultural differences. The exemplary view most countries have of Canada stands as a testament to the fact that it is a free, peaceful and tolerant nation.

Going back to my encounter at the market, I wasn’t stirred by the cashier asking me where I was really from. Canadians come in all shapes and sizes, and each one of us has a unique story that has brought us here. My story traces back to Sri Lanka so it would make sense to say so. However, based on my upbringing and the values instilled in me, I would not do myself justice if I omitted the fact that I am Canadian. Do not be afraid to know where you are from and what you can do to stay in sync with your origins. However, do not forget where you are now and what you can do to move forward and contribute to your country.

Alex Gunaseelan

Alex Gunaseelan