After almost ten years of saying good bye to Tamil class at school, I had the opportunity of visiting several Tamil classrooms in Singapore in July 2012 to talk about the World Tamil University Youth Conference. Bright and cheerful kids in school uniforms made me feel nostalgic for a few moments. Suddenly, it also brought back memories of my Tamil teacher from middle school. I realized how odd a memory it was, because I had not really thought of her in the last ten years.

In Chennai where I went to school, Tamil was one of the options under the compulsory ‘mother tongue’ classes. The other available language options were Hindi and French. My father, a Tamil enthusiast was very adamant that I had to learn Tamil at least until the tenth grade, which is when students wrote their secondary school leaving examinations. I remember pleading with my parents to switch over to French which seemed a much easier option mostly because of my Tamil teacher. Whenever I told them I did not like my Tamil teacher and thus, my Tamil classes they would give me (what seemed to me at that time!) long lectures about the importance of learning one’s mother tongue.

Whenever I think of an adjective to describe Tamil teachers in Tamil Nadu, I can only think of ‘strict’. This is why, ten years later when I stood in a secondary class room in Singapore I was still overtaken by a sense of great relief of having ‘escaped’ learning Tamil under her by transferring my second language to French in high school. I remember the long discussions with my friends of not having to encounter her ‘strictness’ ever again in my life. It is funny in an unnerving way, to think that the ‘Tamil period’ in secondary school and my Tamil teacher have scarred me to such an extent that I still do have recurring nightmares about not having finished pages and pages of Tamil homework when I am really stressed.

In Tamil Nadu, it is fashionable to chastise students for not choosing Tamil as their mother tongue at school. Those who choose to learn other languages are labeled ‘disloyal’ and contributing to the death of a great language. While loyalty remains a matter of personal choice and perception, these accusatory judgments are worth examining so that it leads to some productive dialogue. More often than not, when a child in secondary school wants to switch over to another language in high school, the reason for the switch is to score higher marks that would make the student more competitive for the process of college admissions. Loyalty does not even strike the mind of these kids as the much as the pressure of working towards the much coveted seat in a university. In the context of Tamil Nadu, this would mostly mean admission to an engineering degree course, which remains a very popular career choice.

Perhaps, loyalty could play a role in determining the choice of study of Tamil when there is genuine love and connection with the Tamil language. Today when most of the schooling systems are taught in the English medium in Tamil Nadu, the bulk of this responsibility lies with the Tamil teacher. The Tamil teacher at an English medium school is really the first person who has the power to cultivate a sense of love for the language. In Tamil Nadu, a school going student hardly has any real exposure to the language besides this forty five minute time slot that is allocated every day. Within this slot, he/ she has to pay attention to the syllabus and cultivate a love for a language which is not the medium of instruction in other classes at school. There could be some exceptions where parents try to imbibe their children with a love for Tamil. However, the lack of time and the pressures of a competitive school system where success is measured through percentiles scored in exams, many parents could probably consider this as a waste of time.

My Tamil teacher was brilliant in the way she taught the subject and I still have vivid memories of her teaching Silapathigaram in the ninth standard. Her curt and blunt demeanor would adopt a more approachable aura when she began decoding the difficult verses in class. It was almost as if she used to become a different person when she taught us Tamil poetry. However, the way in which I (and several others of my cohort) approached her class was that of a collective fear- mingled- hatred that her “strictness” cultivated in us.

And strangely, that strictness was somehow intricately linked to her being a ‘Tamil’ teacher. All through my school life, I always remember that my English/ other subject teachers were a happy go lucky bunch but never my Tamil teacher. As a child, I could hardly understand why one had to be “strict” and force so much “discipline” on children just because you were a Tamil teacher. But as an adult, I can understand all the anxiety and the insecurity she could have felt when she had to live out her chosen career of a Tamil teacher. In the Great Academic Chain of Being (in relation to Tamil Nadu), Tamil school teachers occupy the lowest rung. To even imagine a scenario where you chose a career out of pure love for the language and having to teach it to kids who have no little/ no interest and with very little monetary satisfaction seems like a fate worse than death. But this is probably what she faced every day. Possibly, the only way to be taken seriously and be validated in that kind of situation is to enforce ‘discipline’ on children. The fact that this enforced discipline comes to be equated with learning Tamil subconsciously in young children is something that is not thought through.

My friend Jayasutha often reminds me of the saying ” Tamil soru podathu” (tr: Tamil will not provide you with a living). It is important and necessary then, that one needs to think of Tamil as the kozhambu (tr: curry) in a vazhai elai sapadu (tr: banana leaf meal). Her argument is when jingoist Tamil patriots argue that Tamil is dying and that youngsters are responsible for this phenomenon follow the line of thought that Tamil is a wholesome entity that can survive without any effective interaction from any mainstream culture(s) even in the contemporary global world. These Tamil enthusiasts, well intentioned as they are in their efforts to preserve Tamil fail to recognize that Tamil needs to interact and adapt itself with other cultures to survive in today’s world. This is often not counted as an enriching experience in their essentialist ideas of the growth of Tamil.

Tamil teachers who teach in school (especially in TN) often buy into this idea, mostly because they are a product of this idea. They have clearly demarcated divisions about how to measure a person’s interest levels in Tamil. If a child speaks in Tamil without any influence of English, he/ she is lauded with praises and is showcased as the model for others to follow. But this model itself is so elitist with no grounded view of the effect of globalization that permeates our lives. That ‘model child’ soon outgrows the interest after actually learning about monetary benefits of translating that love/ interest into an actual career.

So, two years ago, when I went to schools in Singapore and interacted with these kids in their Tamil classrooms I was jealous.

I was jealous of kids who are effectively bilingual and of the camaderie that they shared with their Tamil teacher, whom they affectionately call ” Asiriyar“. They were excited to participate in WTUYC 2012 and seemed to enjoy discussions that relate to Tamil.

In a situation that we have ourselves created where we constantly push Tamil to a position that does not offer any monetary benefits for the person who wants to teach it in school, how are we even thinking of blaming youngsters who do not speak/ read Tamil, who should have necessarily inculcated a love for the language during their childhood?

Movies like Kattradhu Tamizh play around with the fact that Tamil will not provide you with a satisfactory career in a world that is corporate driven. There is no refuting this claim. It is indeed the truth. But there are larger points of contention that we need to tease out from this situation. The fact remains that this situation stems largely out of a self enforced bubble that does not take into account the place we have allocated to the learning/ inculcating a love for the Tamil language. Additionally, nobody tells you how important it is to be bilingual and excel in both English and Tamil. In Chennai, amongst my age group I know of no bilingual people who can read and write Tamil and English with the same fluency. In school, it was more or less accepted that you excel in Tamil in a way that you would score high marks and that was about it.

So, maybe it really is time we break out of that elitist stereotype of Tamil that we have manufactured for ourselves, starting with the Tamil school teacher.

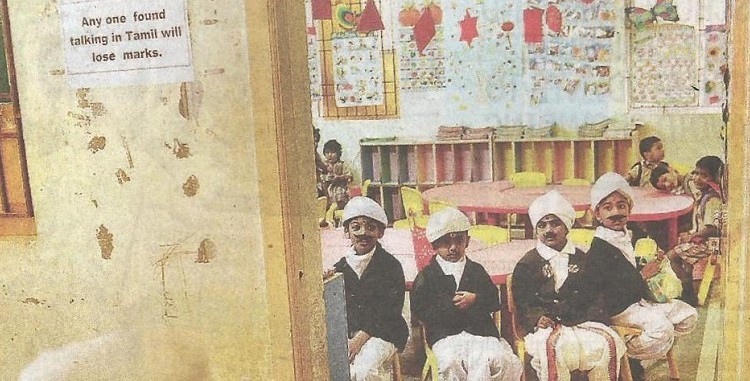

The feature image originally appeared in the December 12th, 2012 Times of India newspaper.

Vasugi Kailasam

Vasugi Kailasam